Babies cry. That sentence sounds simple, but for many parents it becomes a central puzzle: why does my otherwise content newborn suddenly scream for hours? Colic is one of those mysterious, heart-wrenching phenomena that leaves families exhausted and anxious. In this article we’ll explore colic through one particularly important lens — the infant gut. We’ll look at what the gut might be doing, what science knows (and doesn’t know), how to spot clues that point to gut-related causes, and practical steps parents and caregivers can take to help soothe the baby and find answers. Along the way I’ll share actionable information, plain-language explanations of medical ideas, and a few reassuring reminders: you are not alone, and colic usually improves with time.

Many people think of colic as simply excessive crying, but it’s more nuanced than that. Colic usually appears in the first weeks of life, peaks by about six weeks, and often eases by three to four months. Those months, though, can feel like forever. Understanding possible gut-related contributors gives parents a direction to investigate: dietary factors, gut microbiome imbalance, allergies or intolerances, intestinal gas or motility issues, and even acid reflux. Not every crying infant has a gut problem, and not every gut issue will present the same way. We’ll walk through the signs, the science, tests your pediatrician might consider, and practical management strategies that can reduce stress and improve the baby’s comfort.

My aim is to be thorough and practical. I will avoid overwhelming medical jargon, but I will explain the rationale behind tests and treatments so you can have informed conversations with your healthcare team. Let’s begin by defining colic, then dive into the gut-related causes, how they are evaluated, and what you can try at home or discuss with your doctor.

What Is Colic? A Clear, Practical Definition

Colic is often defined by the «rule of threes»: crying for more than three hours a day, for more than three days a week, for more than three weeks, in an otherwise healthy and well-fed infant. While that helps frame the problem, it’s not a hard diagnostic rule — clinicians also look at the pattern of crying, the infant’s growth, and whether there are other warning signs like fever, poor feeding, or weight loss.

Crying linked to colic tends to occur at predictable times (often late afternoon or evening), may be intense and high-pitched, and is sometimes accompanied by signs such as abdominal distension (a rounded belly), drawing up of legs, clenched fists, and passing gas. Parents frequently describe a sense that the baby is in pain and can’t be consoled. That perception is important — infants who cry like this deserve careful evaluation.

Not all excessive crying is colic. Distinguishing colic from other causes such as infection, structural problems, neurologic issues, or hunger is the pediatrician’s job. When the cause seems tied to the digestive tract rather than an infection or another neonatal condition, we say the colic has a gut-related cause.

How the Infant Gut Differs from an Adult Gut

The infant digestive system is a work in progress. Two points matter for understanding colic: immaturity of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract and how the gut interacts with the immune system and the brain.

When babies are born, their intestines are still developing motility patterns — the waves of muscle contraction that move food along. Those immature movements can lead to gas trapping or cramping sensations. Similarly, the mucosal lining and immune cells in the gut are learning to respond appropriately to new proteins and microbes. That learning sometimes produces exaggerated responses, like sensitivity or inflammation.

Another major difference is the nascent microbiome — the community of bacteria and other microbes in the gut. Babies start life with few microbes, and their microbiome diversifies over the first months and years. Factors like birth mode (vaginal vs cesarean), breastfeeding vs formula feeding, antibiotic exposure, and environment shape that community. Emerging research connects certain microbiome patterns with increased crying and colic, though this research is still evolving.

Finally, the gut-brain axis — two-way communication between the gut and the central nervous system — is active from early life. Signals from the intestine can influence a baby’s perception of discomfort and their stress responses, making gut-related issues a plausible contributor to colic behavior.

Common Gut-Related Causes of Colic

The list below outlines gut-related possibilities that clinicians consider when an infant has colic-like symptoms. Each child is different; many cases of colic do not have a single identifiable cause but rather a combination of factors.

Cow’s Milk Protein Allergy (CMPA)

Cow’s milk protein allergy is an immune-mediated reaction to proteins found in cow’s milk. It can occur in breastfed infants (through proteins transmitted in the mother’s milk) and in formula-fed infants. Symptoms vary but can include fussiness, vomiting, blood in the stool, eczema, and sometimes colic-like crying. CMPA is more common in infants with family histories of eczema, asthma, or allergies.

Diagnosis often involves an elimination trial (removing cow’s milk protein from the mother’s diet if breastfeeding, or switching to a hypoallergenic formula) and watching for improvement. In some cases, specific allergy testing or referral to a pediatric allergist may be helpful.

Lactose Intolerance (Primary vs Secondary)

True lactose intolerance due to lack of lactase enzyme is rare in young infants (primary congenital lactase deficiency is extremely uncommon). However, secondary lactose intolerance can occur temporarily after an intestinal infection or inflammation that reduces lactase activity. Symptoms include watery diarrhea, bloating, and discomfort that could fuel colic-like episodes. Management focuses on treating the underlying cause and, if needed, short-term lactose-reduced feeds under medical guidance.

Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (GERD)

Spit-up is normal in infants, but when reflux is frequent and accompanied by pain, poor weight gain, or breathing problems, it may be diagnosed as GERD. Reflux can irritate the esophagus and make feeding and lying down uncomfortable, provoking crying and arching of the back. Careful assessment is necessary because reflux can mimic colic and sometimes coexists with other gut issues.

Behavioral and feeding modifications — smaller, more frequent feeds, positioning changes, and thickened feeds in select cases — are often first-line strategies. Medications are used selectively and typically for specific indications under pediatric supervision.

Excess Gas and Intestinal Motility Problems

Gas accumulation and altered intestinal motility are common suspects in colic. When peristalsis is immature, gas can become trapped and cause cramping-type discomfort. Babies may draw up their legs, pass gas frequently, or have a visibly distended abdomen. These issues often improve as the gut matures but can be managed symptomatically with strategies that help release gas and encourage regular bowel movements.

<h3:Intestinal Hypersensitivity and Visceral Pain

Some infants may have increased sensitivity to normal intestinal sensations — a phenomenon sometimes called visceral hypersensitivity. The same amount of gas or movement that would be barely noticeable to others could be perceived as painful or distressing by the hypersensitive infant. This sensitivity may relate to the developing nervous system and is influenced by genetics and early life experiences.

<h3:Gut Microbiome Imbalance (Dysbiosis)

The gut microbiome plays a growing role in understanding colic. Several studies have found differences in the gut bacteria of colicky infants compared with non-colicky infants — for example, lower diversity or increased abundance of certain bacteria. Probiotics, especially Lactobacillus reuteri in some trials, have shown benefit in breastfed infants with colic in reducing crying time. However, evidence is mixed and more research is needed to identify which infants may benefit and which probiotic strains work best.

Signs That Point to a Gut-Related Cause

Not all crying is linked to the gut, but these signs raise the possibility that the GI system is involved:

- Patterns of crying associated with feeding (worse after feeding or during feeding).

- Visible bloating or a distended belly.

- Pulling up of legs and obvious discomfort after feeding.

- Frequent spit-up or vomiting beyond typical infant reflux.

- Loose stools, mucus, or blood in the stool.

- Poor weight gain or feeding refusal.

- Eczema, visible allergic symptoms, or a strong family history of allergies.

If you notice any of these signs, it’s reasonable to discuss gut-related causes with your pediatrician. They will take a history, perform an exam, and may ask about feeding patterns, stool characteristics, family allergies, and growth.

How Pediatricians Evaluate Gut-Related Colic

Evaluation starts with a clear history and a focused physical exam. Your pediatrician will ask about feeding (breast or formula), how much and how often your baby feeds, the character of regurgitation or spit-up, stool patterns, and the timing and triggers of crying. Growth charts are critical — steady weight gain reduces the likelihood of a serious underlying problem.

Beyond the basics, the clinician may consider:

- Trial of dietary changes (elimination diet for breastfeeding mothers or switching formula types).

- Targeted testing for cow’s milk protein allergy if symptoms suggest it.

- Referral for allergy or gastroenterology consultation when warranted.

- Testing for infections (stool studies) if diarrhea or fever is present.

- Observation or video recordings of crying episodes to evaluate behavior and triggers.

In most cases of straightforward colic, extensive testing is not done because colic is usually benign and self-limited. However, when red flags are present — such as blood in stool, failure to thrive, fever, severe vomiting, or neurologic signs — further investigation becomes necessary.

Management Strategies: Gentle, Evidence-Based, and Practical

Managing colic often involves a combination of strategies. The goal is to reduce the infant’s discomfort and the caregiver’s stress while ensuring no serious condition is missed.

Feeding Adjustments

If you are breastfeeding, your pediatrician may recommend a maternal elimination diet if cow’s milk protein allergy is suspected. This involves removing cow’s milk and sometimes other common allergens from the mother’s diet for a trial period (usually 2–4 weeks) to see if the baby improves. Such diets should be undertaken with support from a healthcare provider or dietitian to ensure maternal nutrition remains adequate.

For formula-fed infants, options include switching to a hydrolyzed formula (proteins broken into smaller pieces) or, in confirmed CMPA, an amino-acid-based formula. Thickened formulas are sometimes used for reflux, under guidance.

Probiotics and Microbiome Approaches

Probiotics are live microorganisms that may help restore balance in the gut microbiome. Some studies, particularly with Lactobacillus reuteri DSM 17938, have shown reduced crying times in breastfed infants with colic. Results are less clear for formula-fed babies and across different strains. Probiotics are not risk-free for premature or medically complex infants; discuss with your pediatrician before starting.

Prebiotics and synbiotics (combinations of prebiotics and probiotics) are areas of ongoing research. Feeding choices that promote a healthy microbiome — such as breastfeeding when possible — are recommended.

Positioning and Soothing Techniques

Practical measures can provide real relief. These include:

- Holding the baby upright after feeds and using paced feeding techniques for bottle-fed infants to reduce air swallowing.

- Using gentle tummy massage or bicycle leg movements to encourage gas release.

- Applying warm compresses or placing the baby on the caregiver’s chest for skin-to-skin contact, which can soothe both baby and parent.

- Trying white noise or rhythmic motion (e.g., rocking, stroller rides) that mimics womb sensations.

These techniques won’t cure an underlying allergy or reflux, but they often reduce distress while other evaluations proceed.

Medications

Medications have a limited role in treating colic itself, but they are used when specific diagnoses are made. For example:

- Antacids or proton pump inhibitors are used in confirmed GERD cases with significant esophagitis and feeding refusal, though they are not routinely recommended for uncomplicated colic.

- Lactase drops or lactose-free formulas may help in temporary secondary lactose intolerance.

- Simethicone (anti-foaming agent) has been widely used, but evidence of benefit is weak.

Any medication use should be guided by a pediatrician, weighing potential benefits and risks.

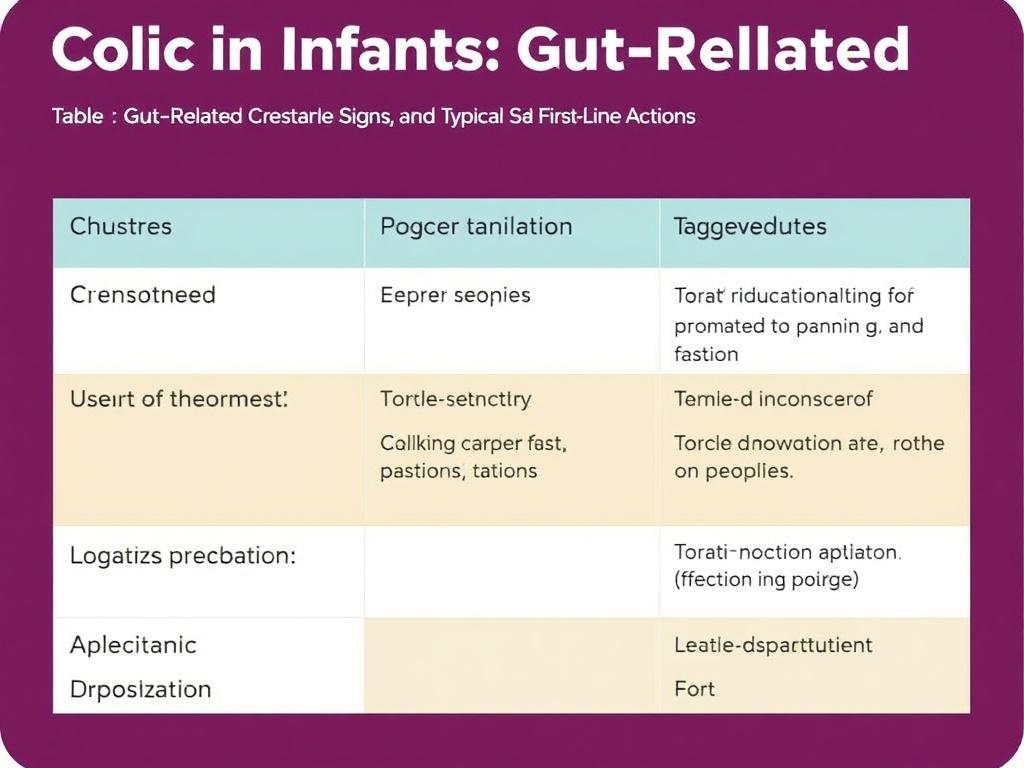

Table: Common Gut-Related Causes, Signs, and Typical First-Line Actions

| Possible Cause | Typical Signs | First-Line Actions |

|---|---|---|

| Cow’s Milk Protein Allergy (CMPA) | Crying with feeds, eczema, blood/mucus in stool, poor weight gain | Trial maternal elimination diet or switch to hydrolyzed/amino-acid formula; monitor response |

| Lactose Intolerance (secondary) | Watery diarrhea after feeds, bloating | Treat underlying infection/inflammation; consider temporary lactose reduction |

| GERD | Frequent spit-up, arching during feeds, feeding aversion | Feeding modifications, positioning, trial thickened feeds; meds if severe |

| Excess Gas / Motility Issues | Distended belly, pull-up legs, passing gas | Feeding technique changes, tummy massage, allow time for maturation |

| Microbiome Imbalance | No unique outward signs beyond crying; may co-occur with other GI symptoms | Consider probiotics (discuss strains), support breastfeeding, avoid unnecessary antibiotics |

When to Try an Elimination Diet or Formula Change

Parents often ask when it’s reasonable to try changes like a maternal elimination diet or switching formulas. Here are practical pointers:

- If the infant has severe symptoms such as blood in stool, persistent vomiting, or poor weight gain, speak with your pediatrician promptly; a directed dietary trial may be recommended.

- If crying is the main issue but there are additional clues (eczema, family allergies, excessive spit-up), a brief elimination trial under medical supervision is a reasonable option.

- Trials should be long enough to see an effect (often 2–4 weeks), and changes should be made one at a time so you can identify what works.

- For breastfeeding mothers, elimination diets can be nutritionally restrictive; consider support from a lactation consultant or dietitian.

Remember: if a diet change helps, reintroduction under medical guidance is important, because infants may outgrow an allergy.

Practical Home Strategies to Reduce Gas and Discomfort

Small adjustments can make big differences day-to-day. Try these simple steps:

- Feed in an upright, calm environment and burp the baby multiple times during and after feeds to minimize swallowed air.

- For bottle-fed infants, use bottles designed to reduce air intake and experiment with slower-flow nipples.

- After feeding, hold the baby upright for 15–20 minutes and avoid vigorous bouncing right away if reflux is suspected.

- Use warm compresses or a warm bath to relax abdominal muscles and promote gas release.

- Practice tummy massages in circular motions and bicycle-leg exercises to help move trapped gas.

- Maintain a soothing routine for the evening hours when colic often flares — dim lights, quiet, predictable actions can lower overall stress.

These approaches are safe and often help, even when the underlying cause is not fully clear.

When to Seek Emergency Care

Most colic is distressing but not an emergency. However, seek urgent medical attention if your baby has:

- High fever or a very high-pitched or weak cry.

- Difficulty breathing, bluish skin, or choking spells.

- Refuses almost all feeds and cannot keep fluids down.

- Signs of dehydration (very dry mouth, very few wet diapers, sunken fontanelle).

- Blood in stool or vomiting blood.

If you’re ever unsure, trust your instincts — call your pediatrician or local emergency services. Prompt evaluation can rule out serious conditions and relieve anxiety.

The Role of Parental Stress and Soothing Responses

Colic doesn’t just affect the infant; it reverberates through the whole family. Parental stress, exhaustion, and feelings of helplessness are common and understandable. The infant can pick up on parental tension, which may amplify crying. Strategies to support caregivers are therefore part of treating colic:

- Take safe breaks. Place the baby in a safe sleep spot and step away for a few minutes to breathe, call someone, or rest.

- Share duties with a partner, family member, or trusted friend, even if only for short windows to allow caregiver recovery.

- Seek support groups or counseling if feelings of depression or anxiety arise; postpartum mood disorders are treatable and common.

- Keep a diary of crying episodes to help healthcare providers identify patterns and guide evaluation.

Remember: caring for your well-being directly helps your baby.

Prevention: What You Can Do Early

While you can’t prevent all cases of colic, certain practices may reduce the likelihood or severity:

- Exclusive breastfeeding when possible, as it supports a beneficial microbiome and reduces exposure to cow’s milk proteins — but formula feeding is a valid choice and many formula-fed babies do perfectly well.

- Careful use of antibiotics only when needed, since antibiotics can disrupt early microbiome development.

- Gentle feeding techniques to minimize swallowed air and overfeeding.

- Support for parents (education, rest, and community), as caregiver well-being affects infant comfort.

These steps help the gut and the family. They are not guarantees, but they build a healthier foundation.

Latest Research and Promising Directions

Scientific understanding of colic is evolving. Areas of active interest include:

- Microbiome profiling to identify infants at risk and to personalize probiotic strategies.

- Better characterization of immune-mediated feed responses to differentiate true allergies from intolerance.

- Non-pharmacologic therapies that modulate the gut-brain axis, such as targeted probiotics, prebiotics, and behavioral interventions.

- Understanding genetic and developmental contributors to visceral hypersensitivity.

While promising, much of the research is still preliminary. That means clinicians must balance enthusiasm for new treatments with the need for solid evidence and safety, especially in very young infants.

Common Questions Parents Ask

Parents frequently have similar questions when facing colic. Here are clear answers to the most common ones.

Is colic a sign of a serious problem?

Usually not. Most colic resolves by 3–4 months and does not indicate long-term harm. However, persistent warning signs like poor weight gain, blood in the stool, or fever should prompt immediate evaluation.

Will changing formulas help?

Sometimes. If a baby has a cow’s milk protein allergy or intolerance, switching to a hydrolyzed or amino-acid formula can greatly reduce symptoms. For many infants with nonspecific colic, formula changes may not help and can add stress.

Do probiotics work?

Some studies show benefit for certain probiotic strains (notably Lactobacillus reuteri in some trials) in breastfed infants, with smaller or mixed effects in formula-fed infants. Probiotics are generally safe in healthy term infants, but speak with your pediatrician before starting.

How long will this last?

Colic often peaks at 6 weeks and improves by 12 weeks, usually resolving by 3–4 months. There’s wide variability; some babies improve sooner, others later. Support during this period is crucial.

Practical Checklist for Parents Visiting the Doctor

A short checklist can make clinical visits more productive:

- Record crying patterns: timing, duration, triggers, and remedies that help.

- Note feeding details: breast vs formula, volume, frequency, and issues during feeds.

- Track stool patterns: color, consistency, presence of blood or mucus.

- List any family history of allergies or eczema.

- Bring a video of a typical crying episode if possible — it can be very informative.

Being prepared helps your pediatrician make informed recommendations.

Conclusion

Colic is frustrating and emotionally draining, but understanding gut-related causes sheds light on possible pathways to relief. The infant gut is immature, sensitive, and still being colonized by microbes — conditions that can lead to discomfort visible as prolonged crying. Causes like cow’s milk protein allergy, reflux, lactose intolerance, gas, motility differences, and microbiome imbalances each deserve consideration, and often the most effective approach blends careful medical evaluation with gentle, practical measures at home. Keep in close contact with your pediatrician, seek help when red flags appear, and prioritize both your baby’s comfort and your own well-being. Colic usually resolves with time, and with the right support and strategies, you and your baby can get through this challenging phase together.

Читайте далее: